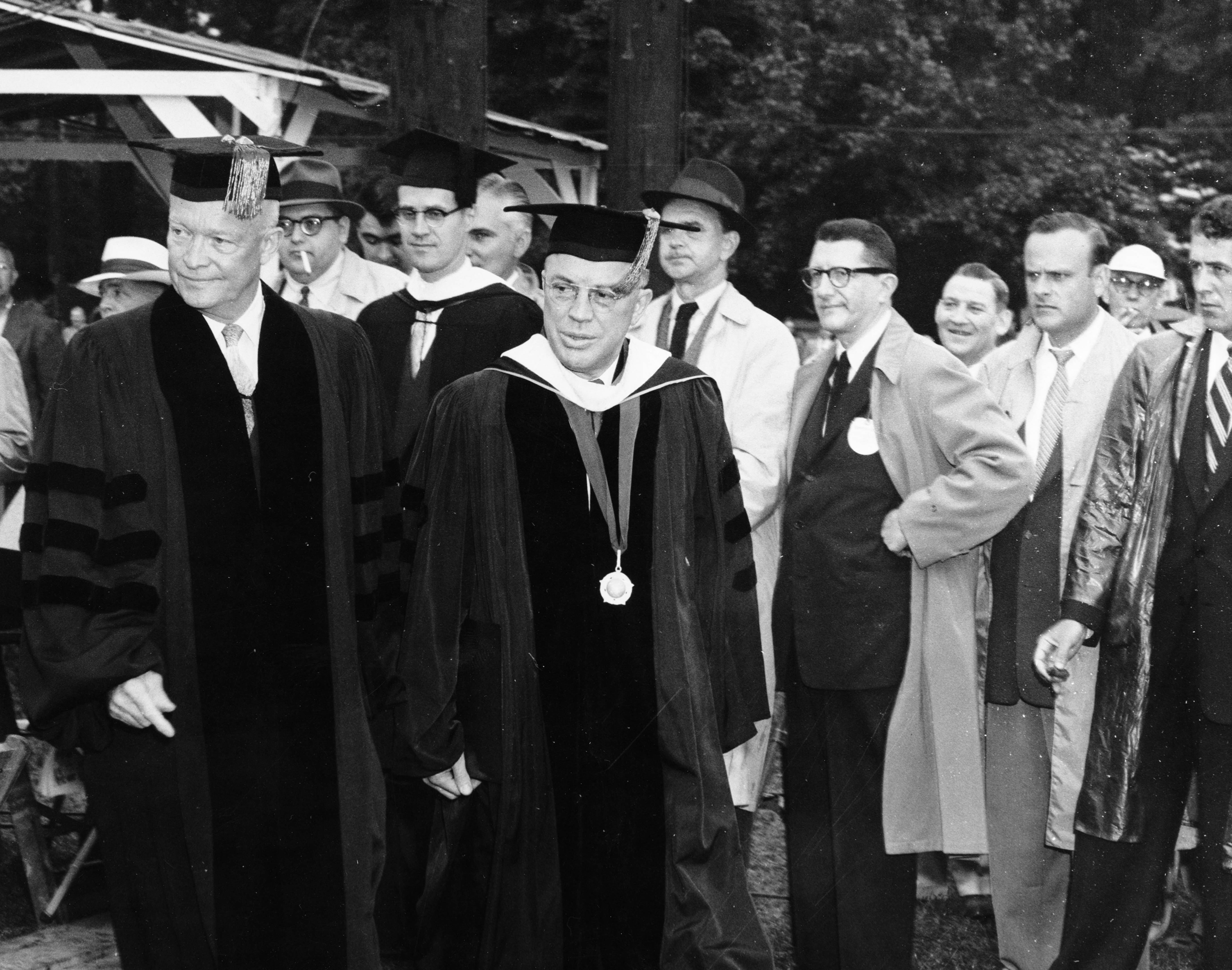

Fifty-nine years ago today, on June 9, 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower addressed the centennial graduating class of Penn State, where his brother, Milton, was president of the university.

Two things were on the President’s mind that afternoon, nuclear energy and general education.

Stalin had died in 1953 and the Cold War was beginning to escalate, but Eisenhower was more concerned that day to emphasize the emancipatory possibilities of nuclear energy than its destructive capacity. Earlier that morning he had inspected the first atomic reactor built on a university campus for research purposes, and the first half of his speech was dedicated to outlining a plan to offer research reactors to “free nations who can use them effectively for the acquisition of the skills and understanding essential to peaceful atomic progress.”

Even so, the specter of nuclear war was never far from his mind. He presents himself as a reluctant but determined warrior, building nuclear warships “because we must,” but preferring to build atomic-powered merchant ships for peace.

This tension between war and peace, annihilation and emancipation, conflict and cooperation had Eisenhower thinking more broadly about the human condition:

As nuclear and other technological achievements continue to mount, the normal life span will continue to climb. The hourly productively of the worker will increase. How is this increase in leisure time and the extension in life expectancy to be spent? Will it be for the achievement of man’s better aspirations or his degradation to the level of a well-fed, well-kept slave of an all powerful state?

Indeed, merely to state that question sharply reminds us that in these days and in the years ahead the need for philosophers and theologians parallels the need for scientists and engineers.

Whether those graduates gathered at New Beaver Field that morning heard in this statement anything more than a strong political critique of Soviet totalitarianism is difficult to say.

But given the 69 credits of general education the students had to complete to graduate, including 12 credits of ancient or modern foreign language, 6 credits each of history, literature, philosophy, and music or art, 1 it is possible that they would have heard in Eisenhower’s appeal to increased “leisure,” the ancient Greek idea of “scholē,” which means free time–that is, the time we have to act and live liberated from the necessities of life that compel us to labor.

Indeed, the Greek “scholē” becomes in Latin, “schola,” and finds its way into English as “school.”

By invoking the idea of “leisure time,” Eisenhower invites us to consider this important line from Aristotle’s Politics: “the first principle of all action is leisure [scholē],” or perhaps better, “schooling.” 2 Schooling is that liberated time in which students are empowered to turn their attention to broader questions of human meaning and purpose, questions that are capable of orienting thoughtful action.

Eisenhower’s insistence that philosophers and theologians are as necessary as scientists and engineers is an eloquent recognition of the importance of this liberated time as an opportunity to cultivate in students a more expansive, we might even say general, understanding of the world and their place in it.

It is no surprise that in 1955, those general education credits were offered by the College of the Liberal Arts, for schooling in the liberal arts is free time, the time of freedom, in which students are liberated to learn what it is to live well.

In 1955, as humanity was coming to terms with its ability to annihilate itself completely, Eisenhower was at pains to emphasize the importance of an integrated approach to liberal education:

What we need is general education, combining the liberal and the practical, which helps a student achieve the solid foundation of understanding–understanding of man’s social institutions, of man’s art and culture, and of the physical and biological and spiritual world in which he lives. It is an education which helps each individual learn how to relate one relevant fact to another; to get the total of relevant facts affecting a given situation in perspective; and to reason critically and with objectivity and moral conscience toward solutions to those situations or problems.

I repeat: this kind of education is sorely needed in this country–and throughout the world.

The repetition was for amplification, but perhaps not only for those gathered at New Beaver Field in 1955.

Perhaps these words repeated here fifty-nine years later might speak again to those of us working together to craft a revised general education curriculum designed to ensure that students learn the intellectual and practical habits of integration that will enable them to make a better world for their communities and themselves.

And perhaps by the 60th anniversary of those centennial commencement exercises, by June 9, 2015, we will have a new general education curriculum at Penn State that will enact something of that sorely needed education of which Eisenhower spoke so eloquently in 1955.

- Here are the relevant pages from the 1955 Penn State Bulletin.

- Aristotle, Politics VIII.3, 1337b32-3.

This should be of interest to Gen Ed at Penn State, Liberal Arts Voices, and The Pennsylvania State University.