Next week I am giving a lecture on Plato’s Gorgias at Boston College for the Boston Area Colloquium for Ancient Philosophy. The title of the lecture is Attempting the Political Art.

Prior to the lecture, I will hold a seminar in which we will focus on those passages in the Gorgias in which truth is at stake as a political question. The seminar, entitled Socrates, Plato and the Politics of Truth, will begin with that strange passage from the Gorgias in which Socrates claims:

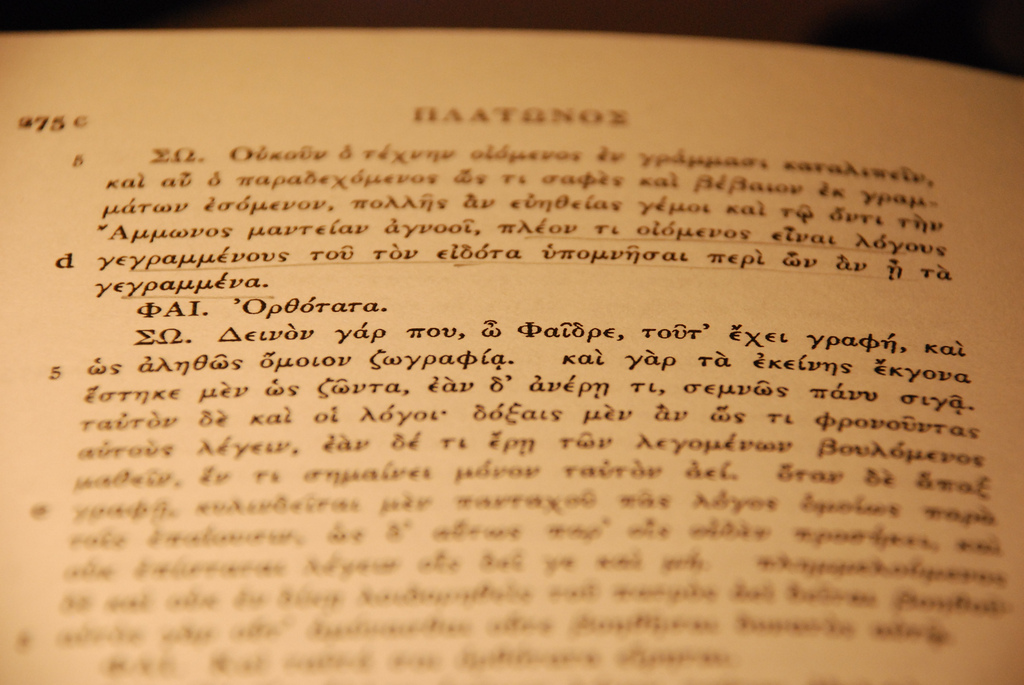

I think that with few Athenians, so as not to say the only one, I attempt the political art truly [ἐπιχειρεῖν τῇ ὡς ἀληθῶς πολιτικῇ τέχνῃ] and I alone of those now living do political things [πράττειν τὰ πολιτικὰ]; for it is not toward [πρὸς] gratification that I speak the speeches I speak on each occasion, but toward [πρὸς τὸ βέλτιστον] the best, not toward [πρὸς] the most pleasant … (Gorgias, 521d6-e2).

This passage invites us not only to ask about the nature of the “art” that Socrates claims to be one of the few to attempt, but also to consider the question of the political nature of Platonic writing.

The distinction between the ways of saying endemic to Socratic politics and the ways of writing endemic to Platonic politics will frame the discussion in the seminar. In an essay on Plato’s Protagoras that has recently appeared in Epoché, I have thematized this distinction in terms of the “topology of Socratic politics” and the “topography of Platonic politics.” (For a more detailed discussion of the distinction, see Digital Dialogue 31: Shame and Justice, and more recently, see, Digital Dialogue 44: The Apology.)

For those students and faculty who will attend the seminar, we will focus our attention on the following passages in addition to the one cited above:

- 453a8-b3: Where Socrates claims that he and Gorgias are each the sort of person who wants to know “the very thing for which the logos exists.”

- 453c2-4: Where Socrates connects the proper way to proceed with a way of speaking that makes things as evident as possible.

- 457c4-d5: Where Socrates distinguishes between a way of speaking animated by a desire to win and one committed to making the matter at hand evident.

- 458a2-5: Where Socrates insists that he is as happy to be refuted as to refute.

These passages point to the nature of the relationship between Gorgias and Socrates, which, I argue, grows through the dialogue into a kind of friendship rooted in a shared desire for the truth. This can be heard in these passages, which we will also consider:

- 463a1-5: Where Socrates is empowered by Gorgias to continue his discussion with Polus so as to make what they have been discussing evident. This leads to the discussion of the difference between a techne and an empeiria, an art or a knack.

- 464e2-465a6: Suggests the nature of a techne, as Socrates uses it in the dialogue.

- 500c1-503a9: Where Socrates articulates the beautiful rhetoric associated with philosophy.

- 506b2-3: The final words Gorgias speaks in the dialogue, in which he encourages Socrates to continue the logos even when Callicles refuses to respond any longer.