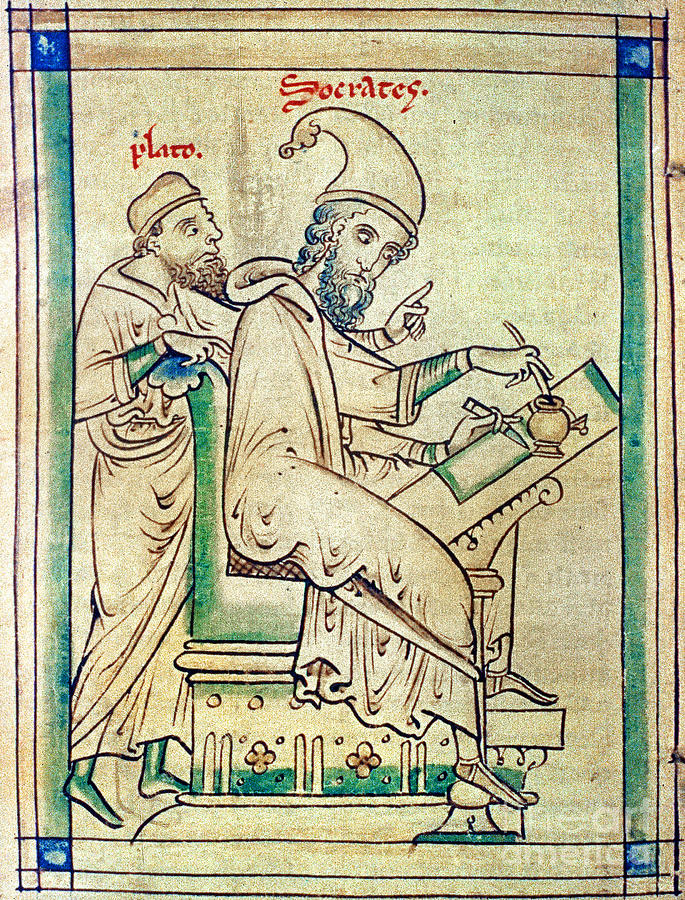

This drawing from Mathew Paris (1217-1259), made famous more recently by Derrida’s disquisition on it in The Postcard, appears in a 13th century manuscript that contains a series of fortune-telling tracts. 1 More specifically, it appears in a manuscript held by the Bodleian Library in Oxford, MS Ashmole 304, 31v.

Now, with the generous permission of the Bodleian Library, the image will also appear on the cover of my enhanced digital book, Socratic and Platonic Political Philosophy: Practicing a Politics of Reading.

Derrida was attracted to the image, which he discovered on a postcard in the giftshop of the Bodleian library during a visit on June 4, 1977, because it seemed to confirm for him something he had long surmised, namely, that writing is prior to speaking. The image stopped him dead, he said,

with a feeling of hallucination … and of revelation at the same time, an apocalyptic revelation: Socrates writing, writing in front of Plato, I always knew it … 2

Derrida plays with the image throughout the first half of the The Post Card, creatively deconstructing it.

But Matthew Paris’s drawing has a deeper and richer play of significations than even Derrida’s deconstruction is able to draw out.

Michael Camille’s essay, The Dissenting Image, sets the drawing into its 13th century medieval context where we find other drawings with similar iconography. Specifically, Camille suggests:

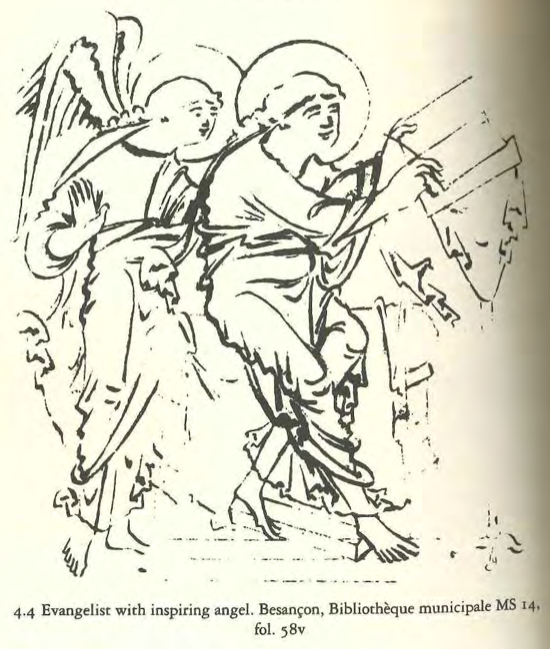

The fundamental model “behind” the Socrates and Plato image is the Evangelist portrait in which the inspiring man-angel symbol stands behind St. Matthew as he writes at his lectern. 3

This background suggests that Plato’s figure should be given a kind of divine and sovereign status in relation to Socrates.

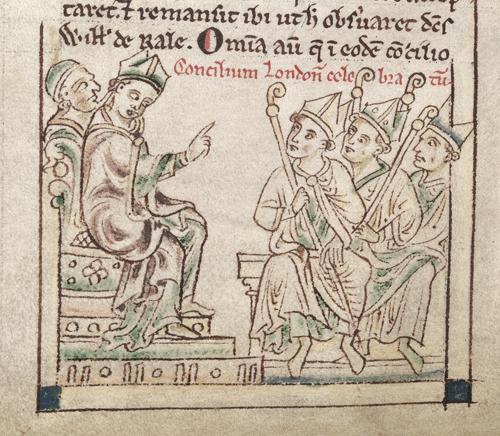

And yet, even this connection does not allow for a univocal reading of the image, for Plato’s position, his rather stern look and prodding right-hand finger, resonate with another of Paris’s favorite visual tropes, that of the evil counselor or whispering devil. 4

(Thanks to Dr. Georg Strack for pointing me to Paris’s “The Council of London” found in London, Royal 14 C VII, f. 126.)

Whatever else the image of Plato and Socrates does, however creatively deconstructed or astutely situated back into its thirteenth century context, the drawing opens the question of the ambiguous relationship between Socrates and Plato, and more deeply, of that between speaking and writing.

These are the very questions that animate my book, a book that will now carry this enigmatic image on its cover, inviting those who open it, or enter into it digitally, to consider how to read these figures in their relation to one another.

If, as Camille suggests, “Plato’s gesture ‘indicates’ (from indicare, to point out), guides our eyes across the page to the functional squares of the fortune-telling diagram opposite,” and if, as Camille goes on to point out, “the ‘ready to write’ gesture of Socrates helps signal the beginning,” 5 then it is perhaps fitting that on the cover of this book these two figures point in the same direction: to the beginning of a reading that might indeed open the space for the emergence of a hermeneutical community.

- Camille, Michael. “The Dissenting Image: a Postcard from Matthew Paris.” In Criticism and Dissent in the Middle Ages, edited by Rita Copeland. Cambridge University Press, 1996, 115–150.

- Derrida, Jacques. The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Trans. by Alan Bass, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987, 9.

- The Dissenting Image, 124

- Ibid., 127

- Ibid., 139

3 Comments