To be published or to be read, that is the question scholars increasingly face.

Although publications with reputable university presses or journals continue to be the cornerstone of the tenure and promotion process, many remain inaccessible to a broad audience, bound up, as they often are, in paper volumes or locked behind paywalls required by the outmoded business practices of scholarly publishers.

Take this recent experience as illustrative of the situation scholars committed to Open Access face.

An article I recently wrote was published in the The Bloomsbury Companion to Aristotle, edited by Claudia Baracchi. It includes articles from a number of notable scholars and I am very happy to be included among them.

Even so, however, the volume is expensive. As of this writing, the hardback is $137.74 (though the Kindle edition is a bargain at $88.49). I am told they plan to release a lower priced paperback soon, it is difficult to see how the article will find wide readership locked away in a codex behind such a prohibitive pay wall.

After posting an abstract about the article on my blog and linking to the book, chuk and dirk commented that the cost of the book was a significant barrier for them. This prompted me to ask Bloomsbury if I could publish a .pdf copy of my article on my blog.

In response, Bloomsbury said that they could not permit this because of concerns about piracy, but they did create a website to make my article available to read until May 2014.

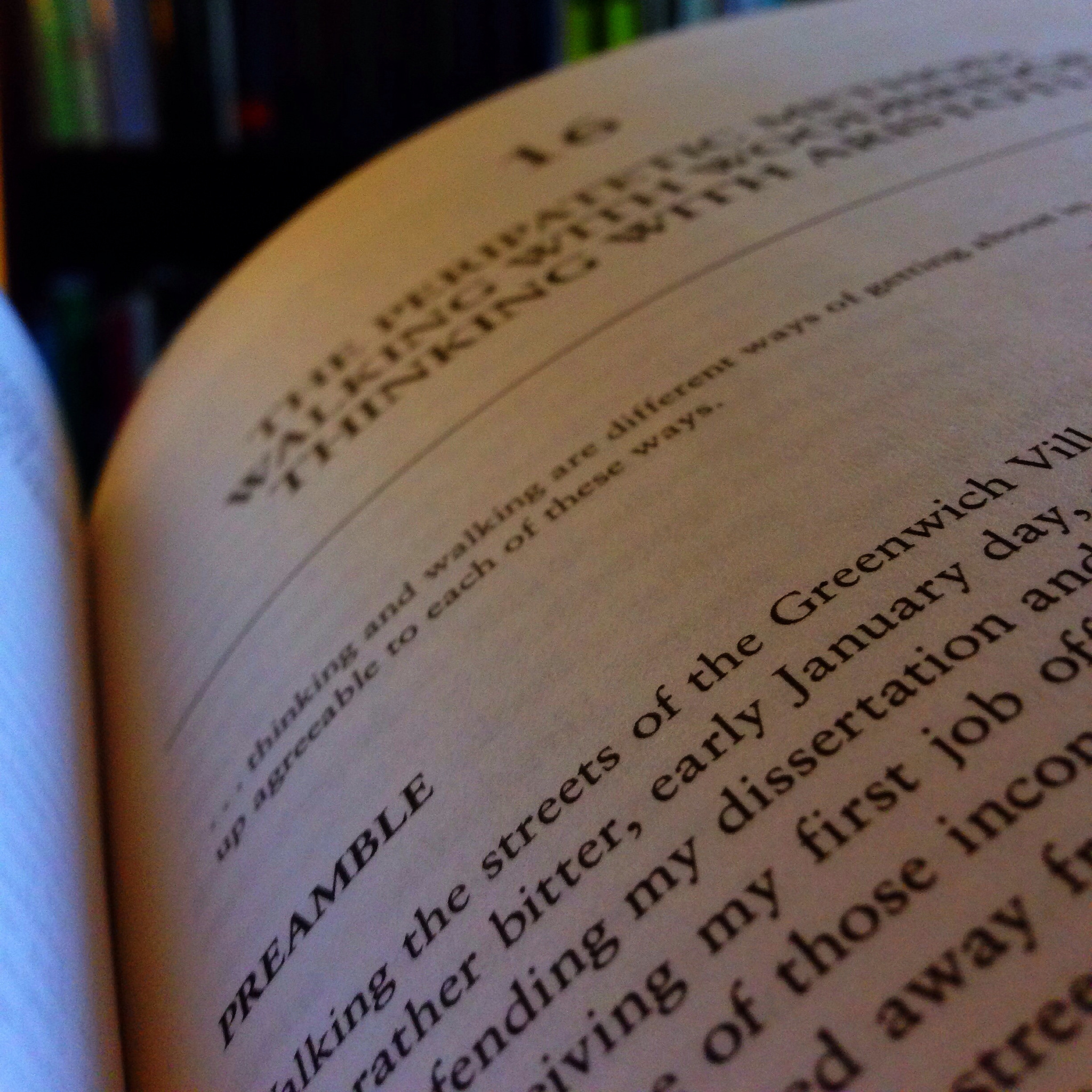

I would be interested in your thoughts on the website they created for this. Take a moment to visit the link to The Peripatetic Method: Walking with Woodbridge, Thinking with Aristotle.

While I very much appreciated the creation of this site, I was struck by a number of its limitations. First, the resolution of the text on screen is low, detracting from the reading experience. Second, there is no way to download the article for reading later — which, of course, was part of the purpose of creating the site as opposed to allowing me to post the .pdf. Finally, there is also no way to view other articles in the book, even partially, nor a way to purchase the book, should a reader be interested and willing.

Don’t misunderstand, I appreciate the creation of the site as a response to my request. Even so, it didn’t provide what I really want: to give full access in an ongoing way to anyone interested in reading my work.

In thinking about possible alternative models, I wondered if it would be possible to allow me to publish my article as a .pdf file if I would agree to post a link to the book along with it. That link might direct people to a digital version of the whole book, where interested readers could read excerpts of the other articles in the volume. Perhaps the publisher could give those who access the book through that link a discount on the purchase of the physical book. Even one or two sales would likely offset whatever cost is lost by opening my article to a wider public.

The business model here would be to leverage the social media and web presence of authors to drive interested readers to a specific volume. Bloomsbury’s creation of the website for my article goes some distance down this road, but it doesn’t go far enough. The website is only available through May and, although they have allowed me to post the Word document of my chapter here, the reader is not able to download and annotate the published version.

I have embedded the final draft of the essay below, with the page numbers of the published version in square brackets in the text so readers can easily cite the published version. The full bibliographic information is this:

- Long, Christopher P. “The Peripatetic Method: Walking with Woodbridge, Thinking with Aristotle.” In The Bloomsbury Companion to Aristotle, edited by Claudia Baracchi, 311–326. 1 edition. Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

If you are a member of the Penn State academic community, you have access to the volume itself through the Penn State library, so I have also posted it to Scholarsphere with access limited to those with a Penn State access ID: The Peripatetic Method via Scholarsphere.

If you do read the full volume, I hope the excellent design, editorial and creative work that went into its production is obvious. The design and editorial labor was undertaken by the press and Claudia Baracchi — and it was no small task to do it as well as they did. However, the lion’s share of the creative labor, of whatever new knowledge is articulated in this volume, was undertaken by the contributors.

The disparity between the work we put into the volume and the value we receive in return is a gap worth considering.

A book chapter in an edited volume with top scholars in the field certainly has a positive, but difficult to quantify, impact on a scholarly profile. That impact somehow translates into decisions concerning promotion and salary increases, but the direct monetary value of a single book chapter is minimal. Monetary value is, however, only one aspect of the value of publishing, a minor one from my perspective. More important for those of us committed to Open Access and concerned for the wide dissemination of ideas is the public dimension of publication — the degree to which publishing involves making something public. As a faculty member at a land-grant institution whose mission in part is to provide “unparalleled access and public service to support the citizens of the Commonwealth,” it seems incumbent upon me to ensure that my work is shared as widely and as publicly as possible. Yet, when the barriers to public access are set as high as they are in this case, the number of possible readers diminishes significantly.

It seems here that its being published is hindering the work from being more widely read.

The Peripatetic Method: Walking with Woodbridge, Thinking with Aristotle

not to be too impertinent, but aren’t you at a point in your career where you can put aside worrying about promotions and such in favor of knowledge and inquiry and the good that comes from sharing your learning and thinking freely?

i was unable to get anything to load at the publisher-hosted link you provided, with two different web browsers.

there’s so much machinery here. buttons and widgets and logins and applets and notifications and tags and etc. etc. etc.

on some scientists’ websites, rather, web pages, a vision of the use to which academics could put the internet before its commercialization and web 2.0-ification and social-media-ation, is still visible. and to a large extent it still consists in just throwing up low-profile copies of things they want others to be able to use.

to me your average blogger.com blog or low-frills wordpress blog expresses that spirit better than much that i’ve seen going by the ‘digital humanities’ or ‘open access’ tags. or even the occasional institutionally-overseen faculty web page, like those of the u. of chicago faculty, which often just contain links to copies of their articles.

what is it about the humanities that makes that freedom to share seem so daunting? a risk?

ilyaoblomov I think I fixed the publisher hosted link, so that should work now.

I publish at this point in my career both to have my work reviewed and commented upon by my peers and to participate in the academic system of credentialing by which decisions about promotion and raises are made. But a post like this is really designed to open a discussion about that system of credentialing and the way the business practices of publishers interfaces with it. As an administrator, I participate in that system too – both as someone who assesses the work of others and who has his work assessed.

I try to keep the basic page of this site relatively clean, but I like the buttons and widgets that allow for conversations like these and provide access to content in different ways.

I don’t share your nostalgia for Web 1.0, but I do enjoy recalling it. Here is a nice post about the design of the early web: http://contemporary-home-computing.org/prof-dr-style/

Thinking a little out loud here with you about the question of humanists and free sharing, one reason for the reluctance might be that our words and ideas are the full extent of our intellectual property; that is, we don’t have a dataset, a lab, or a scientific invention to fall back on should the words and ideas be taken from us. If we simply publish our ideas on our websites without submitting them to the traditional mechanisms of academic credentialing, it is difficult to demonstrate their value in an academic institutional structure that requires that credentialing in order to make informed decisions about merit and value.

I have been thinking and working on alternative models, so this post is broadly speaking, part of that ongoing attempt to work through some of these issues in relation to my own scholarship.

Christopher, are you unable to negotiate limited republishing rights? Have you ever tried? I don’t know your market. But I am wondering whether academics in your position have more bargaining power than realized.

In a way, this post was an account of my failed attempt to negotiate limited republishing rights. Ultimately, I think that probably needs to be negotiated up front, prior to publication. In the future, I plan to be much more intentional about the publishing arrangements into which I agree to enter when I agree to contribute to a volume like this. I agree that academics probably have more leverage than we realize.

cplong Several of my friends in academia are facing this issue as well.

.didiames I am increasingly thinking that I will only publish in venues that are committed to #OpenAccess: http://www.cplong.org/2014/03/to-be-published-or-to-be-read/

Many publishers, esp. in the university press community are philosophically very supportive of OA. The problem UPs face, however, is even as not-for-profits, we have to recover costs. And funding OA in the arts and humanities is a tough row to hoe. As you know, PSUP published an OA monograph series (10 or so vols.) and is hoping to publish a fully OA journal. I also sit on a board for SPARC’s campus-based publishing advisory board, so I am sympathetic. The challenge, though, remains paying the costs. If the humanities had funding like the STEM folks, life would be good, Elysian in fact. Publishing remains “Noble gambling.” If I knew I could sell x number of volumes of a title every time, I could price books quite differently. As it is, publishers still rely on a handful of titles to sell better than expected to cover the losses of those titles that don’t sell as they should.

publisher2b What do you think specifically about the idea of leveraging an author’s online presence to recover some of the costs? The model I am suggesting would be, in effect, for the scholar/author to loan their “brand” to the publisher to try to sell more copies of the book or journal. Perhaps if readers find an OA article from a volume on my site, they would be interested in purchasing the entire volume, perhaps at a discount. I understand that humanities texts don’t often have huge sales, but if publishers came to see their authors as a community of influencers, they might be able to leverage that influence to sell more copies of their books. In exchange, however, authors should request rights to publish their work OA.

cplong publisher2bChris, it might be possible to leverage an author’s reputation/online presence, but it is (1) unlikely and (2) not something that could form the basis of a business model. Discoverability of a website, while possible, is just not the best way to manage scholarly information. Publishers already rely on their authors to promote themselves and their work. Even in the present system, an author’s self-promotion can have an extremely positive influence. The notion that OA leads to more purchases, could be true in some cases, but usually, since the audience for scholarly work is so limited, it is usually not the case. It’s more difficult to find, less stable, less “archivable,” and someone has to pay for that too, right? A lot of work has been done on OA business models. Raym Crow’s work is among the best. http://www.sparc.arl.org/resources/papers-guides/oa-income-models. Publishers are finding, I think, that non-institutionally based researchers are using sites like JSTOR to find information. And while that info can sit behind a paywall at JSTOR, the costs—in the humanities—is not unreasonable. Moreover, material can be requested—free often—via ILL. The issue of author rights v publisher rights hangs in a delicate balance. Most scholarly publishers from a practical standpoint are usually very accommodating to an author’s request. Where they get nervous is when authors want that “practical standpoint” to become a policy. Then the publisher must weigh when does the cost outweigh the benefit. For example, under most book agreements, publishers control translation rights. If an author requests, say, French rights, publishers rarely push back. But if publishers just waived all translation rights, then they’d miss out on that one title in one hundred that might have the potential to be translated.

publisher2b cplong The point you make about individual requests versus establishing a policy (and thus a business practice) is important. I have found that publishers do want, in general, to accommodate my requests.

However, authors, particularly younger scholars, are often just happy to have their work published. As a result, they don’t advocate for OA (or much else for that matter).

As for the cost of archiving, yes, someone has to pay for that, but what some publishers (Springer, for example) are charging (£3000) is obscene. If a author is part of a university, there are often options for archiving (like Penn State’s ScholarSphere). Still, that is not a broad solution. Even if the model is to ask the author to pay, it should be a reasonable amount.

Finally, I think discoverability and an online presence are important precisely because of what you mention – the audience for scholarly work is so limited. But that means that when scholars have already cultivated an online community around their work, that should be of significant value to a publisher. It may be more valuable given the smaller scale of scholarly publications, because the online presence of more popular figures will reach a large audience in any case, but having a smaller, but more committed audience can have a more significant impact on the smaller scale.